1933-2007::The City of Alanville

- Papertown Station

- Mar 10, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 18, 2025

From building a miniature city in the basement to beautifying provincial and national capitals.

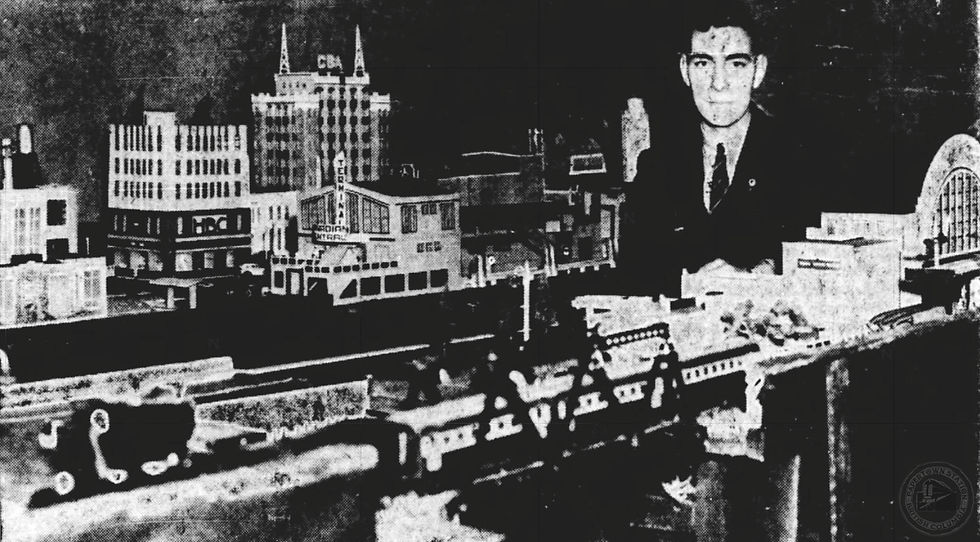

"1939::17-Year-Old Roderick Clack in His City of Alanville"

Photo Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1939)

Victoria, British Columbia

In 1933, a foundation was laid for what would become one of the most intriguing coastal cities in the Pacific Northwest. The miniature city of Alanville, created by 12-year-old schoolboy Roderick Clack of Victoria, British Columbia, started as a simple, crude arrangement of cardboard houses scattered about a toy railroad track. But as Clack continued to build, plan, and revise his little railroad town, something extraordinary began to develop. By 1936, Alanville, named for his younger brother, had grown to the size of a miniature city, occupying 154 square feet of his parents' 179-square-foot basement in James Bay. By 1939, the world Clack had built with cardboard, pieces of glass, coloured sponges, and slivers of wood had grown to the size of a miniature metropolis.

"1936::Alan of Alanville"

Photo Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1936)

Victoria, British Columbia

At 17, Clack's passion for architecture was evident in the details of Alanville. Everything about it had been perfectly scaled at five feet to one inch, making it a special place for guests to explore. Miniature model pedestrians strolled about its beautifully designed business district, where modern buildings towered around a fine harbour and street lamps illuminated their way. Railroad crossings with red flashing lights brought finely detailed trucks and automobiles to a halt as the train zoomed past on its way to an elaborate train station. A warm glow emanated from the firelit windows of elegantly constructed homes in a nearby residential neighbourhood, reminiscent of the Uplands in Victoria. The cathedral, an exceptional building with flying buttresses and stained glass windows, stood tall among the miniature trees as the city's only piece of original architecture. In Allanville, every skyscraper, bank, fire hall, shipping dock, train station, gas station and residence was a miniature replica of a real-life North American structure, with details down to its elevators, mail chutes and rooftop air conditioning systems, all scaled to perfection. Alanville's newspaper, The Right of Way, featured the city's newest buildings and a list of construction sites with notices of temporary road closures or detours. It was distributed regularly to anyone who had personally visited "the great city in the basement" and signed its Visitor's Guestbook.

"If you scale down [the train's] speed it comes to about 150 miles an hour when the power is turned on full, and that's ridiculous." -Young Roderick Clack, on scaling down even the speed of Alanville's train.

"1956::A New Firm"

Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1956) Victoria, British Columbia

Clack's college education began at Victoria's Craigdarroch Castle before transferring to the University of British Columbia (UBC). However, at the outbreak of WWII, he put his education on hold to enlist with the Royal Canadian Air Force and was sent overseas. He was flying Wellington and Halifax bombers across war-torn Europe when he suddenly fell ill with pneumonia. While convalescing in London, he fell in love with his nurse, whom he married shortly before returning to Canada and his education at UBC. In 1953, Clack graduated with a degree in Architecture and Urban Design and spent the next several years in a partnership firm designing award-winning buildings on Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland, many of which still stand today. In 1957, his firm sold out to a Vancouver architect and disbanded while at the top of its game. It had won more local, provincial and national design awards than any other firm in the city. Before the year's end, Clack had taken on Victoria's first official City Planner position and was tasked with developing a Downtown Improvement Plan, which he would later call the awakening of Victoria.

"1958::A Plan for Victoria's Broad Street Pedestrian Mall"

Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1958)

Victoria, British Columbia

Clack had a big job ahead. He began by revisiting a concept laid before the council two years earlier, when Californian engineers were consulted about Victoria's unique traffic issues. They had suggested that Douglas Street be closed to vehicular traffic to allow for a pedestrian-only shopping area. Clack felt it was the right idea but the wrong street and recommended Broad Street instead, which would better align with his new Downtown Improvement Plan. A sketch of his vision appeared in the local papers for Victorians to consider, and an overwhelming response was received in favour of the idea. His Broad Street Mall sketch went national after it appeared on the spring magazine cover of the Community Planning Association of Canada (CPAC).

"Clack's [Broadstreet Mall] sketch is the subject of quite a few interesting comments from Canadian communities." -Eric Beecroft (1958), CPAC National Director in Ottawa

"1962::Clack's Sketch for his New Civic Precinct Plan"

Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1962)

Victoria, British Columbia

After weathering the Great Depression and two World Wars, the city's biggest concern was, above all else, Victoria's revitalization plan. Simply put, they needed to breathe life back into their sleepy city. They voted to tear down the aging City Hall and rebuild a new one on Cathedral Hill (where today's courthouse now stands), but the idea came with an enormous price tag and was later rejected. With a thin budget, they decided to clean up the old City Hall and add a new extension for additional office space. The new Civic Precinct Plan became the affordable alternative to mark Victoria's 100th Birthday, which was fast approaching.

"1962-2023::Victoria's City Hall Extension and Centennial Square"

Photo Clip (left): Victoria Daily Times (1962)

Photo Credits: Bill Halkett (left) Google Earth 2023 (right)

In 1962, the council's Civic Precinct Plan was put into action. Cormorant Street was closed at Douglas Street, and Pandora Avenue was rerouted to tie in with Cormorant Street at Government Street. The city council saved what buildings they could, demolished the ones they couldn't, and created enough space to construct the city's new Centennial Square with its specially designed fountain to honour Victoria's 100th Birthday. It was a plan that aligned well with Clack's Downtown Improvement Plan.

"1963::A Downtown Paint-Up Facelift"

Photo Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1963)

Victoria, British Columbia

Big improvements began with a simple coat of paint. While construction on Centennial Square continued, Victoria's mayor had Clack pick out a two-tone colour scheme to spruce up City Hall. Its newly painted look had immediate results and inspired Victorians to get on board with the city's big clean-up project. Business owners spruced up their downtown storefronts with colour advice from City Hall, and free paint donated by a local manufacturer. When the work was finished, city officials walked the streets, admiring downtown's new look. The great city they thought was lost was slowly being restored. Their excitement would carry them through the plan's next challenge: Bastion Square.

"1972::Victoria's Revitalized Bastion Square Showing Burnes House and the Old Courthouse"

Photo Clip: The Ottawa Citizen (1972)

Ottawa, Ontario

By the 1960s, Bastion Square, one of Victoria's most historically significant areas, had become a dark corridor of warehouses that had long been slated for either restoration or demolition. The provincial government had offered to contribute to the cost of restoring the old courthouse at the corner of Bastion and Langley Streets, but backed away from the project at the last minute, leaving the city at a loss for what to do. An idea was then afoot to tear down the old courthouse and the crumbling Burnes House to make way for a parkade. But as luck would have it, the owner of the Burnes House died just as purchase plans for the property were about to close. His death left the council with no choice but to consider acquiring the land by expropriation, but Clack and other concerned citizens who opposed their parkade plan put up a fight and ultimately saved the buildings and the destruction of the city's historical Bastion Square.

"The plan to locate a parking building in the centre of this district would probably remove forever any hope of restoring the area - at least from a historical standpoint." -Roderick Clack, on Bastion Square being turned into a parkade.

"1964::Victoria's Revitalized Bastion Square"

Photo Clip: Victoria Daily Times (1964)

Ottawa, Ontario

In 1964, Clack and his assistant built a model-sized vision for Bastion Square. The old warehouses would be restored and repurposed, and the open-area promenade would have freshly planted trees and a water feature to support its new maritime theme. But the city would have to complete the project without Clack.

"1966::Roderick Clack Reviewing Proposed Beautification Plans for the Nation's Capital"

Photo Clip: The Ottawa Citizen (1966)

Ottawa, Ontario

In 1965, Ottawa's Federal Centennial Committee contacted Victoria's City Hall, asking to borrow Clack and his extraordinary planning skills on a six-month loan. Clack used the opportunity to resign but promised the mayor he would make himself available to see Victoria's big projects through.

"1966::A Townscape Rediscovered"

Film Credit: (tbd)

After six months as Ottawa's Chief Planner, Clack had his contract extended. Municipalities across Canada soon benefited from his beautification and planning advice as they prepared their cities for the country's Centennial year. He was welcomed everywhere he went, and everywhere he went, a little bit of Victoria went along with him, as shown in a film called A Townscape Rediscovered.

"All of Canada is in debt to Victoria for its pioneer work in restoring and rehabilitating aging buildings of character. If it could be done in Victoria, we thought it could be done across Canada." -John Fisher (1966), Commissioner of the Canada Confederation Centennial Commission

"1974::Clack Returns to Victoria for Inner Harbour Consultation"

Photo Clip: Victoria Times (1974)

Victoria, British Columbia

In 1974, Victoria's city council sought advice from Ottawa regarding their Inner Harbour concerns and arranged to borrow Clack and his unique planning insights from the federal government. After a short visit to Victoria, Clack submitted his recommendations in a report before returning to Ottawa and his new position as Assistant General Manager and Director of Planning for Canada's National Capital Commission. A few years later, after winning international acclaim for Ottawa as a world-class Capital City, Clack accepted an invitation to spend time as an exchange planner in Canberra, Australia's national capital. He retired in 1983 and returned to Victoria, where local planning authorities and advisory boards continued to value his guidance on special city projects. In 2005, his eyesight began to fail, but his vision for Victoria remained firm. When Clack died in 2007, his obituary revealed that he had enjoyed model railroading all his life.

"I suppose I've always been a planner. I remember when I was 12 years old I drew my first plan for revising and revamping the area around the Inner Harbour. It gave me quite a thrill to see that basic plan revived." -Roderick Clack (1921-2007)